The Unimportance of Being Innocent

How can we trust a system that is comfortable with the death of innocents?

“This Court has never held that the Constitution forbids the execution of a convicted defendant who has had a full and fair trial but is later able to convince a habeas court that he is 'actually' innocent.”

So said Justice Antonin Scalia in his dissent In re Davis (2011).

Scalia was correct. The Supreme Court has shown itself to be not merely unpersuaded by a defendant’s ‘actual innocence’, but totally uninterested in it.

As James Martin wrote in America Magazine shortly after Justice Scalia issued this opinion (in which Justice Clarence Thomas concurred):

Let us be clear precisely what this means. If a defendant were convicted, after a constitutionally unflawed trial, of murdering his wife, and then came to the Supreme Court with his very much alive wife at his side, and sought a new trial based on newly discovered evidence (namely that his wife was alive), these two justices would tell him, in effect: “Look, your wife may be alive as a matter of fact, but as a matter of constitutional law, she’s dead, and as for you, Mr. Innocent Defendant, you’re dead, too, since there is no constitutional right not to be executed merely because you’re innocent.”

So, while we can’t fault Justice Scalia on the accuracy of his statement, we might wonder at the moral turpitude that allows someone to hide behind precedent and permit such a clear wrong to continue, especially in a court that has proved itself comfortable with overturning its own precedents 237 times.

Constitutionally unflawed trials

Somehow, those “full and fair trials” that Justice Scalia mentions result in an astonishing number of innocent people languishing behind bars: Of the almost 1.4 million people who have been convicted of a crime and are imprisoned today, it is conservatively estimated that 5% of them are innocent. One in twenty.

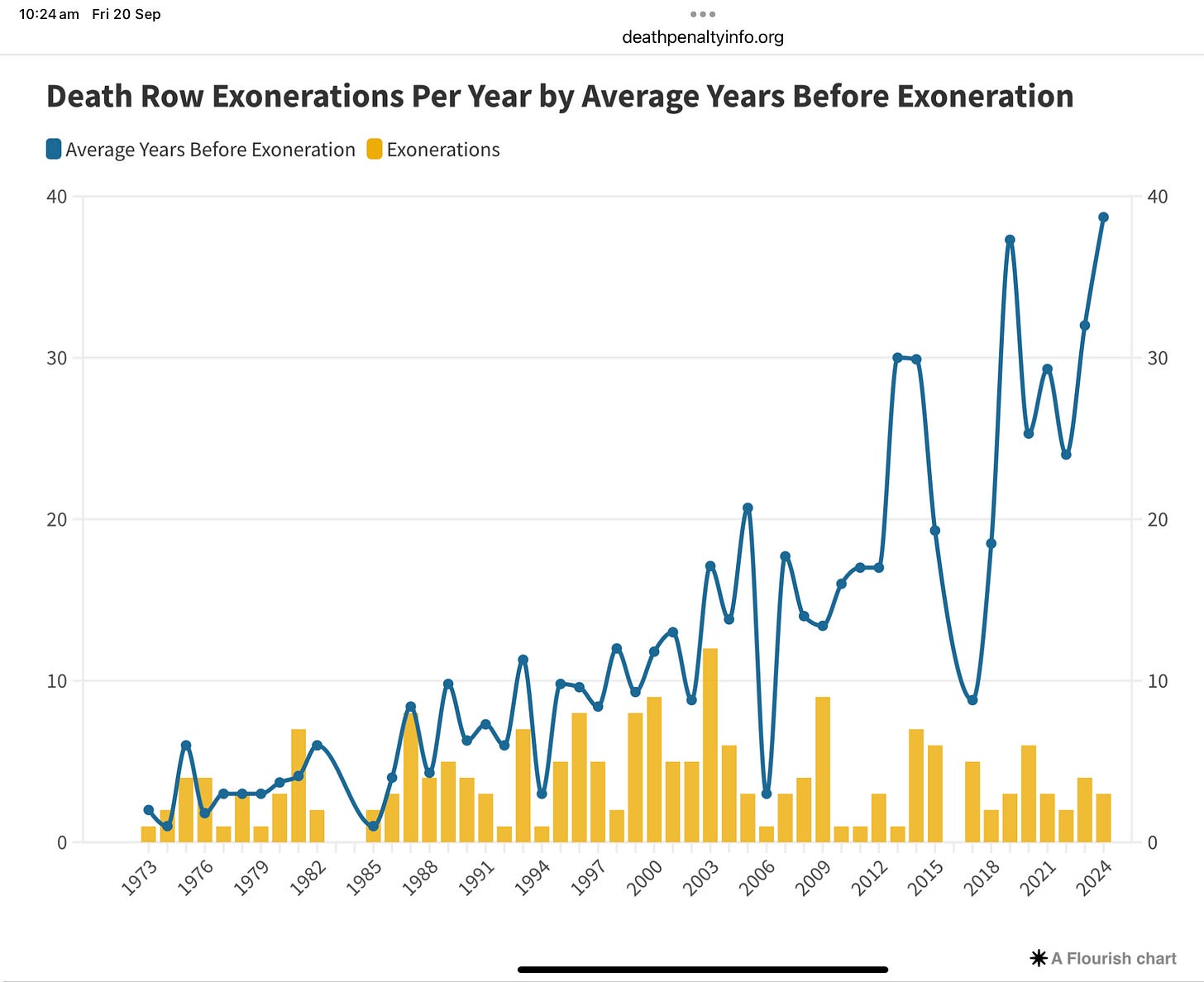

That percentage holds true for those on death row, where trying to prove innocence is an increasingly drawn-out process, as this chart from the Death Penalty Information Center shows:

Trial defense is everything

It is impossible to overstate the importance of having a good defense at your trial. Once a trial court has convicted you, you will face higher courts that are loath to overturn that conviction, especially where a jury is involved, and you will also need to avoid a series of ‘procedural bars’ that choke off your avenues of appeal.

Most poor people cannot afford a good trial lawyer. What they get is a public defender who is likely to be ‘dangerously overworked’ and thus able to give only a fraction of the time needed to present a decent defense.

It’s no surprise, then, that over 95% of cases never even go to trial and are instead determined by plea bargains, a system which saves both time and expense, but which can have a terrible cost, especially for the innocent.

Innocent people agree to plea bargains for a number of reasons: fear of a harsher sentence; intense pressure from prosecutors who offer deals with a very limited ‘expiry date’; a lack of understanding of their rights; mistrust of a system which has proved to treat marginalized communities harshly.

All in all, the justice system can prove a treacherous place for truly innocent people who get poor defense.

In immediate jeopardy

One such person is Marcellus Williams who Missouri intends to execute on September 24th. This will be the third time that Mr. Williams has faced an execution date; in 2017, he came within hours of being executed before receiving a stay.

Mr. Williams is almost certainly innocent. The evidence against him is so severely flawed that the prosecutor, Wesley Bell, has sought to have his conviction overturned. In this he has been thwarted by the Missouri Attorney General, Andrew Bailey, a man who has sought to keep people in prison even after they have been exonerated.

Please give the office of Missouri Governor, Mike Parson, a call before Tuesday 24th September and politely request that he stop the execution of Marcellus Williams from proceeding. The number is 417-373-3400. This link provides a call script and more information.

What are procedural bars?

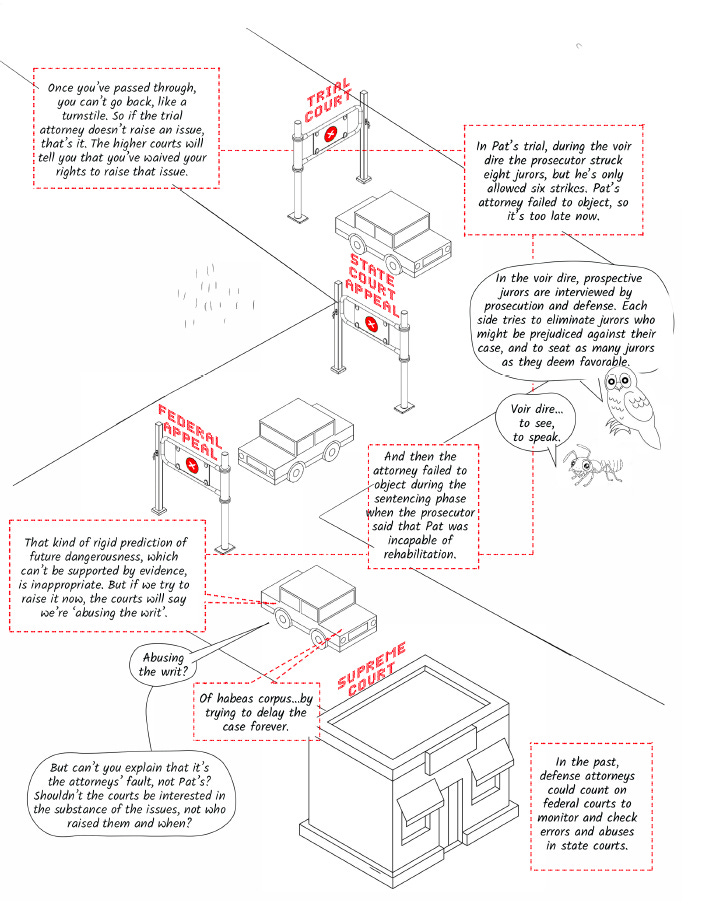

Procedural bars are technical ‘gotchas’ that can prevent a defendant from receiving relief from the courts.

The court system is, essentially, a series of one-way gates. In Dead Man Walking, attorney Millard Farmer explains how this system of rules works to Sister Helen Prejean as they drive to Angola prison together for the first time. Below is a fragment of their conversation as it’s depicted in Graphic Dead Man Walking:

One example of a procedural bar

Before a person can be executed, the governor or a judge must issue a death warrant. The warrant is usually issued after the condemned person has exhausted all their appeals, and it is often a matter of weeks between the issuance of the warrant and the execution.

The Supreme Court has said that execution-related claims—such as a challenge to the method of execution—are premature if an execution warrant has not yet been issued. Therefore, to raise such a claim, the defendant must wait until the execution warrant has been served. However, the same court shows extreme skepticism to appeals raised so late in the process, regarding them as a delaying tactic. They often determine that the claim has been raised too late and that the execution should proceed.

A sad read. Even in less life and death cases, justice does seem to be only possible for the wealthy. Hope I never land in court!

It’s outrageous that actually being innocent doesn’t sway a court. It should not matter that technical time limits for appeals have expired, if there is solid evidence that the defendant is innocent.